Trauma: nonviolent Coping with Injuries

The emergence of a Trauma

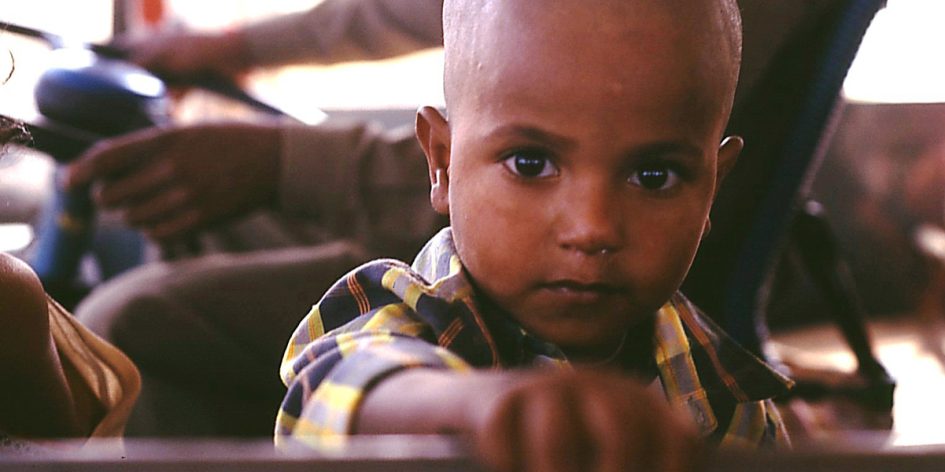

Trauma can be triggered by experiences of violence as well as by an accident, an operation, a stay in the hospital, the sudden loss of a relative, or neglect in early childhood. According to trauma expert and psychotherapist Peter A. Levine, it is the physical feeling of hopelessness associated with fear, that is essential for the development of a trauma.

“When we are acutely threatened, we mobilize enormous energies to protect and defend ourselves. We duck, dodge, turn away, stiffen and contract. Our muscles tense up so that we can fight or flee. But if these activities are ineffective, we freeze or collapse.“1

Blocked survival instincts

External force or a strong inner conflict between opposing drives can inhibit the body’s instinctive escape or defense reactions. In war or natural disasters, for example, the instinctive impulse for self-preservation can often collide with the impulse to save others.

The motor expression of two opposing instinctive reactions can lead to a conflict between agonist and antagonist and thus to immobility. Normally the antagonist relaxes while the agonist contracts. A traumatic conflict may cause both muscles to contract and block each other. This can lead to temporary states of immobility, or even to longer-lasting psychosomatic paralysis.

Psychic freezing

This initial physiological freezing often shifts to the psychological level after the traumatic experience. This is because the psychological system tries to avoid intense feelings of hopelessness and panic at all costs. By avoiding confrontation with his/her own negative as well as positive feelings and emotions, the traumatized person feels trapped in his/her psychological numbness. This is how the typical emotional symptoms of a trauma develop: helplessness, fear, closure, depression, horror, anger, and hopelessness.

In the trap

“We can roughly divide the fear that underlies immobility into two fears: the fear of entering immobility, which is synonymous with the fear of paralysis, trapping, helplessness, and death; and the fear of coming out of immobility, and thus of the intense energy of feelings based on anger. Because of this double embrace […] immobility blocks its own dissolution, so that this state seems to be unbreakable.”2

However, if the therapist succeeds in decoupling fear and immobility, the time for the traumatized person can move forward again. Thereby s/he can interrupt the feedback loop of horror and paralysis.

“The knowledge that everything that happens is finite, and therefore will end sooner or later, makes most experiences bearable. The opposite is also true – we find situations unbearable if we assume that they will never end […]. Trauma is the worst way to experience that something will ‘never end’.”3

Anti-psychotic drugs?

Trauma can manifest itself in sleep disorders, but also in panic attacks, lack of concentration, depressive moods, exhaustion, social withdrawal, and physical symptoms. Complex traumas in early childhood can lead to personality disorders such as borderline. Often Post-traumatic disorders are treated with antipsychotic drugs like mental illness. This means that the symptoms do not have to be questioned in detail. Trauma therapy, on the other hand, can possibly resolve the underlying conflict by linking the symptoms with the patient’s history.

Quick Dispatch

“The increasing use [of psychopharmca] does not reflect the real situation. The questions remain open: […] What are the patients concerned about trying to cope with? What internal and external resources are available to them? How do they calm down? Do they have a caring relationship with their own body? And what do they do to promote their physical sensation of power, vitality, and relaxation? Are they capable of dynamic interactions with other people? Who really knows and loves them and takes care of them? […] Do they feel that their life has meaning? What are they particularly good at? How can we help them to feel that they are in control of their own situation?“4

However, traumatization is not an illness but a human experience rooted in survival instincts; even if not everyone experiences the same situation as traumatic, anyone can be traumatized. Likewise, the psychological consolidation that is a reaction to the use of violence can be dissolved.

Body-awareness

In trauma therapy for instance massage and yoga asanas can successfully improve body awareness and acceptance of emotions. Since traumatization manifests in psychological, as well as physical tension as well as in numbness towards one’s own feelings and body perceptions.

“In yoga, attention is focused on breathing and on feeling from moment to moment. One begins to recognize the connection between the emotional and one’s own body […] One experiments with how to change the way one feels.”5

Subsequent trembling

‘Somatic Experiencing‘, the trauma therapy developed by Peter Levine, is based on the principle of catharsis (the somatic release of blocked survival energies). This somatic catharsis often manifests itself in the trembling and shaking of the entire body.

“This […] ‘trembling’ that people experience in different circumstances and that has many other functions can be a catalyst for authentic transformation and awe. Although the trembling of anxiety does not in itself guarantee the restoration of balance, it can if experienced correctly and under guidance, carry its own dissolution within it.”6

Cathartic body tremors

The nervous system shakes off the tension by the body tremor. This instinctive reaction of the body helps us to restore our balance after threats. The trembling of the body after the moment of terror can, if not interrupted, save us from traumatization.

‘Somatic Experiencing‘ is based on the assumption that in some situations this instinctive restoration of balance is interrupted by external circumstances. By preventing this catharsis, the situation can become traumatic in retrospect. This can occur, for instance, when, on the way to the hospital, an accident victim is tied so tightly to the stretcher, that a cathartic shaking of the body becomes impossible. ‘Somatic Experiencing‘ is about the therapeutic catharsis of the stuck, instinctive reactions.

Minimal movement

The first step is to closely observe the patient’s posture and movements.

“Posture, gestures, and facial expressions of people tell the wordless story of what happened or didn’t happen when they were threatened or overwhelmed. Typical body postures that people have adopted tell us what we need to retrace and dissolve. Therapists [therefore] need to have a precise sense of what compelling instinctive impulses [the traumatized person] […] did not carry out due to a threatening situation.“7

Inconspicuous movements can give an indication of the situation in which the energies have been ‘frozen‘. The therapist first directs the attention of the traumatized person to areas that seem unproblematic to him or her. In this way, s/he gives the patient the opportunity to locate ‘islands of well-being‘ in the body. The patient can return to these unproblematic zones when threatening feelings arise.

Commuting

Peter Levine calls this switching back and forth between anchoring in the presence of the body and evoking minimal doses of traumatic feelings ‘oscillating‘. After anchoring the patient sufficiently in the here and now of the pleasant feeling, the therapist asks him/her to repeat certain movements, that s/he has particularly noticed, very slowly. If the therapist’s intuition was correct, this movement, repeated in slow motion, activates the body’s memory. Then the consciously executed movement leads the traumatized person directly back to the situation in which the movement was frozen.

“By making contact with her non-verbal body posture, Miriam can penetrate the surface of her musings to the story her body tells her and explore it freely. In this way she can feel into the neuromuscular posture that underlies her conflict […] ‘I need more space for me, this is really how it feels’. She waves her arms in front of her body and then stretches them out to the side as if drawing a semicircle in which she can move freely.”8

This makes it possible to separate fear and other strong negative emotions from the biological reaction of immobility. This breaks the feedback loop that constantly reignites the trauma reaction.

Titration

‘Somatic Experiencing‘ is not, as in the cathartic method of Breuer and Freud, about letting the patient relive and verbalize the traumatic situation in every detail. It is rather about the ability, “to revisit a traumatic experience without reliving it […] [this renegotiation] is fundamental to the process of recovery.”9

However, the traumatized person should only be confronted in very small doses with the violent energies triggered by the traumatic situation. Peter Levine calls this ‘titration‘. The term ‘titration‘ comes from experimental chemistry. It refers to the process of mixing a substance. Some substances would cause an explosive reaction when mixed with another substance at once. Therefore they are mixed drop by drop so that they merely cause a soft hissing sound.

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing

The psychologist Francine Shapiro discovered by chance during a walk in the park in 1987 that rapid eye movements have a positive effect on mood. She developed EMDR therapy from this.

“EMDR makes something in the mind/brain accessible, which allows quick access to loosely linked memories and images from the past. This obviously helps patients to see their traumatic experience in a larger context and to put it into perspective.”10

In other words, rapid eye movements create new connections in the brain (as in the REM sleep phase). This enables the integration of the traumatic memory fragments. Similarly, REM sleep activates more distant associations than the waking state.

Above all, the inability to reconnect experiences is, according to Bessel van der Kolk, a prominent feature of post-traumatic stress disorder. Through EMDR the trauma loses its immediacy. This is how the traumatized person can experience memories of the events as something long bygone. However, the EMDR method works much better in patients who were traumatized in adulthood than in patients who were traumatized in childhood.

Systemic therapy

Richard Schwartz developed the ‘Internal Family System Therapy‘ / IFS Systemic Therapy with the ‘inner family’.

“At the heart of IFS is the idea that our mind resembles a family whose members are characterized by different degrees of maturity, irritability, wisdom, and pain. These parts together form a network or system within which changes in one part affect all the other parts.“11

Through traumatization this self-system breaks down, and conflicts between different parts arise. Denied parts In IFS therapy are the ‘banished‘. The ‘manager‘ or ‘fire fighter‘ are parts of the self, that ‘protect’ the collapsed system. Hence, when an event activates banished emotions, the latter appear spontaneously.

Acceptance of inner experiences

‘Acceptance and Commitment Therapy‘ (ACT) is about accepting unpleasant inner experiences. Meditation and mindfulness techniques support the patient, to reduce harmful control- and avoidance behavior and to des-identify with brooding thoughts.

Neurofeedback

Another form of therapy that can help traumatized people is ‘Neurofeedback‘. It uses brain current curves for feedback training. The brain curves are measured in the patient’s brain by electrodes and simultaneously displayed on a screen. The patient thus directly sees the neuronal effects that certain thoughts or feelings have in the brain. Through this direct feedback of the brain’s current pattern, s/he can achieve better self-regulation.

Experience of violence

When the experience of violence has traumatized a person, a nonviolent attitude becomes the greatest challenge. Then it is not only the trauma itself that has to be coped with but also the violence. After all, not every trauma is based on an explicit experience of violence.

Victimhood

Violent traumatization is often passed on over several generations. Similarly, the feeling of victimization is passed on to the next generation. It is therefore important to find an attitude that breaks this chain and allows the traumatized person to end his/her victim existence.

“People can learn to influence and change their behavior, but they can only do so if they feel so secure that they are able to experiment with new solutions. The body does not forget: when traumata are expressed in the form of heartbreaking sensations, our initial aim is to help people out of their state of fight and flight, to reorganize their perception of danger, and to support them in their dealings with others.“12

Rage and fear

By all means, the cycle of anger and fear that traps traumatized people in their panicky paralysis poses the greatest difficulty in overcoming traumas caused by violent experiences. When traumatized persons gradually leave their immobility behind, they often have outbursts of intense anger.

“But because they fear that they might actually hurt others (or themselves), they make great efforts to ward off and suppress this feeling before they really feel it. […] Anger can totally overwhelm us and cause panic. These primitive impulses freeze and then turn inwards so that the natural way out of the state of paralysis is closed to us. […] The vicious circle of intense sensation/anger/fear keeps a person trapped in the trauma reaction.“13

Enemy constructions

Another effect of experiences of violence is the fear and massive loss of confidence that such an event almost inevitably brings with it. People traumatized by violence either lose all faith in their ability to love, or they divide others into friends and foes. In conflicts, this leads to the demonization of the (supposed) opponent.

“Because of the tendency towards a strong ego relationship, which results from its biological origins, fear often occupies all of one’s thinking, making it difficult to think of anything other than oneself and one’s immediate surroundings as long as the fear lasts.“14

Dissociation, flashback, re-staging

Above all, victims of violence, especially sexual violence in childhood, tend to lose contact with themselves. They look at their body as if from the outside and disconnect from the events. However, this psychological protection, which is useful in itself, can mean that traumatized people can no longer assess their body’s warnings correctly. As the traumatized person misinterprets the emotional signals, s/he easily becomes a victim of violence again. A flashback of the traumatic situation can lead to an inundation of emotions of fear or anger. It can in turn become a trigger for violence.

“Flashbacks and re-staging are in a certain sense worse and harder to bear than the trauma itself. […] People with PTSD can have a flashback at any time, whether they are awake or asleep. It is impossible to predict when this will happen again, or how long such a situation will last.”15

Overriding the inhibition threshold

A flashback puts the traumatized person in the same frenzied horror that s/he experienced when emerging from his/her immobility after the trauma. Through flashbacks, soldiers commit terrible war crimes against civilians. They often lose control of their actions once they have returned to civilian life. The majority of traumatized war veterans use drugs and alcohol to try to forget the traumatic impressions and deal with insomnia.

Furthermore, the psychologically evoked lowering of the inhibition to kill during military training may encourage the aggressive loss of control, experienced by veterans. Once psychological manipulation, or biochemical intervention has lowered this innate inhibition threshold, it is very difficult to get rid of the demons that have been summoned.

Forced to keep silent

Moreover, until the Vietnam War, veterans could not speak publicly about their war traumas, fears, and aggressions. Society simply hushed up their suffering or interpreted it as personal ‘weakness’.

“Denying the consequences of trauma can do great damage to the social fabric of society. Refusal to deal with the damage caused by the [First] World War and intolerance of ‘weakness’ played an important role in the rise of fascism and militarism around the world in the 1930s.”16

The multiple demoralization caused by war and the disinhibition of aggression often haunt veterans for the rest of their lives. They destroy their lives and those of their families. In 2005 alone, more than 6000 US veterans took their own lives. That is more deaths than the US army suffered in the Iraq war.

War traumas

However, perhaps the war demons of aggression, fear, and self-hate can be tamed precisely by a nonviolent attitude (supported by trauma therapy). “The U.S. Civil Rights movement, [Martin Luther] King explained, did not cause outbursts of anger but ‘expressed anger under discipline for maximum effect. This discipline of conserving our anger is not an act of repression. When we do it correctly, it enables our anger to be converted into creative power. Nonviolence is the power released by the conversion of a negative drive.“17

The involvement in nonviolent movements indicates the positive effect of nonviolence on traumatized soldiers, for instance the association ‘Iraq Veterans against the war‘.

“Nonviolence is perhaps best described as a practice of resistance that becomes possible, if not mandatory, precisely at the moment when doing violence seems most justified and obvious. So […] we can think of nonviolence not simply as the absence of violence […] but as a sustained commitment, even a way of rerouting aggression for the purposes of affirming ideals of equality and freedom.

My first suggestion is that what Albert Einstein called ‘militant pacifism‘ might be rethought as ‘aggressive nonviolence’. That will involve rethinking the relation between aggression and violence since the two are not the same.“18

Author: Eva Pudill

Estimated reading time: 13 minutes

Related Articles:

>> The Violence of the Caste System

>> Ishvara Pranidhana: Mysticism as a nonideological Zone

>> Nonviolent Resistance Movements Worldwide

>> Disgression: Power & Violence

>> Disgression: Humanity & Human Rights

>> Writing as a Trauma-coping Strategy

>> Taking leave from Self-Victimization

>> Ressentiment: the Circling of Thoughts about missed Reactions

>> Dealing with Shadows and Demons

>> Catharsis in Ritual, Tragedy, and Performance-Art

Questions & Answers

What trauma therapies are there?

> Somatic Experiencing read more

> EMDR – Eye-Movement-Desensitization and Processing read more

> IFS – Inner Family Systemic Therapy read more

> ACT – Acceptance and Commitment Therapy read more

> Neurofeedback read more

> Hypnotherapy read more

> Trauma-sensitive Massage read more

> Trauma-sensitive Yoga read more

> Feldenkrais read more

> Shamanism read more

> Trauma-sensitive Mindfulness-meditation read more

> Writing & Art Therapy read more

What indicates that a situation has been perceived as traumatic?

External force or a strong inner conflict between opposing drives can inhibit the body’s instinctive escape or defense reactions. In war or natural disasters, for example, the instinctive impulse for self-preservation can often collide with the impulse to save others … read more

What are trauma responses?

The most common responses are fight, flight, or freeze. The initial physiological freezing often shifts to the psychological level after the traumatic experience. This is because the psychological system tries to avoid intense feelings of hopelessness and panic at all costs … read more

How do I know I’m traumatized?

Trauma can manifest itself in sleeping disorders, but also in panic attacks, lack of concentration, depressive moods, exhaustion, social withdrawal, and physical symptoms. Complex traumas in early childhood can lead to personality disorders such as borderline … read more

Does the body remember trauma?

Trauma is always stored in the body. Therefore, the gestures of the body can, such as in ‘Somatic Experiencing‘, provide information about the origin of the trauma. Inconspicuous movements can give an indication of the situation in which the energies have been frozen … read more